I thought today would be a good day to post an article of mine that was first published in Sent by the King, the journal published by La Société des Filles du roi et soldats du Carignan.

A Fille du Roi and a Métis Country Wife: My Truly Canadian Story

On the 15th of February 1637, in the parish of St-Éloi in Rouen, France, a baby girl named Louise was baptized. Sometime around 1805, near “the Polar Sea” (Hudson Bay) in what is now northern Manitoba, a girl named Margaret was born. What connects these women’s stories? A look at their lives, and the roles they played, gives us a glimpse into the importance of women throughout Canada’s history.

Louise was the daughter of Pierre Senécal and Françoise Campion. The family lived in Rouen, a city about 135 km northwest of Paris, in the area of France known as Normandy. Her mother died when she was only eight years old, and she had two older sisters. We don’t know the circumstances of her life in France. Was her family poor? What did her father do for a living? Was she educated?

What we do know is that on the 25th of September 1667, Louise arrived at Québec City on the ship St. Louis de Dieppe. The ship had left Dieppe, a town on the Normandy coast of northern France, in June, then had stopped in La Rochelle, a seaport city on the west coast of France, making a journey of more than three months to Québec.

Louise was a Fille du roi, one of the hundreds of young women who came to New France with the assistance of King Louis XIV under a plan to populate the young colony during the period of 1663-1673. Simply put, there were not enough young women for the men currently in New France to marry and to produce children to populate the colony.

How brave did a young woman have to be to set foot on such a journey? Was the prospect of a life in New France more appealing than her situation in France? Was she yearning for adventure? The women had their trip paid for, and received certain provisions, and often a dowry upon marriage in New France. They were expected to marry but had a personal choice of their mate.

Among the provisions they received before the journey were clothing, sewing needles, knives, and a bonnet. Once they married, they would be given food and livestock.

The ship Louise travelled on, St. Louis de Dieppe, belonged to the Compagnie des Indes Occidentales (East India Company). The company was commissioned by the King to transport the Filles du roi to New France. This particular journey included 90 young women and 100 engagés (men on contract to work in New France). The women, some of whom were from Paris, boarded at Dieppe or La Rochelle. Louise probably boarded in Dieppe, as it was closer to where she lived.

We do know something of the conditions of this voyage, because 20 young women from Paris complained about their treatment! On the 17th of June they appeared before a notary in Dieppe and signed an Acte de Protestation! They complained that upon arriving there they had not received the accommodation they had been promised.

Jean Talon, Intendant of New France when they arrived in the colony, wrote in October to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Ministre de la Marine in France:

“The girls assured me that from the moment that they had set sail, they received neither honesty nor humanity from the officers aboard, who caused them to suffer greatly from hunger, giving them nothing but a light meal in the morning and at night nothing for supper but a little hard tack and nothing more.”

Louise was not one of the protestors, but we could assume she endured the same conditions if she had boarded in Dieppe. When the ship arrived in Québec City, 24 engagés and 16 Filles du roi were sick.

It took only five days after arrival for Louise to accept a proposal and agree to a marriage contract in which her dowry was listed as 100 livres. On the 6th of October 1667, at Notre-Dame, the church in Québec City, she married Pierre Guilbault. She claimed to be only 24, although her baptismal record indicates she would have been 30 years old.

As Thomas J. Laforest tells us in his book Our French-Canadian Ancestors, Pierre had been unlucky in love. Twice previously, he had signed marriage contracts, but the marriages never took place. After his marriage to Louise, Pierre and Louise lived in Charlesbourg, a section of Québec City, and raised their four children. It appears that Pierre’s fourth marriage, after Louise died,also ended in an annulment (in 1693).

Of course, we have no way of knowing what their marriage was like. When their youngest child, Elizabeth, was baptized on the 17th of December 1679, Louise stated she was not living with Pierre but that he was the father. However, they must have reconciled as the 1681 census finds them together in Charlesbourg. Their household boasts 30 arpents (about 25 acres) under cultivation, 8 cattle, 2 horses and 1 gun.

The Filles du roi are considered the “Founding Mothers” of Québec. Peter J. Gagné includes a chart in his book, “King’s Daughters and Founding Mothers”, that specifies how many descendants each woman had by the year 1729. Louise Senécal had 61 at that point.

One of her descendants was Marie Anne Labelle (1776-1845) who married Louis Amable Hogue (1769-1801) in 1795 in St-Vincent-de-Paul, the parish in Laval, near Montréal. Her father granted them land and Louis was listed as an “agricultier”, i.e., farmer. Louis died young and he and Marie Anne had only three children.

Their first, born on the 14th of July 1796, was a son, also called Louis Amable. This son, the 3x great-grandson of Louise Senécal, would leave Québec and go out west. After having fought in the War of 1812, Amable, as he was known, went to work as a laborer for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). At that time the Governor of HBC was Sir George Simpson, and Amable became one of his paddlers.

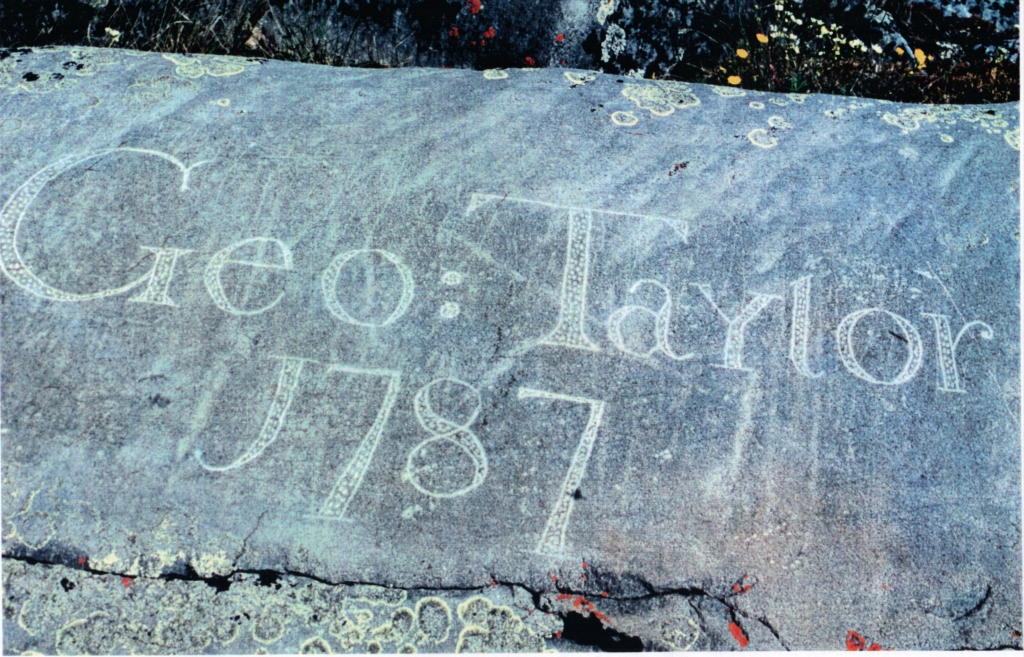

At this point, we join Margaret’s story. She was born to “Jane”, a Cree woman, and George Taylor, an Englishman, in about 1805. George Taylor was a sloop master for the Hudson’s Bay Company, in charge of some of the ships that sailed between London and Hudson Bay. These wooden sailing ships carried trade items from London and then brought furs back. According to the HBC records, George was in the areas of Churchill, also known as Fort Prince of Wales, and York Factory, both in what is now Manitoba, as well as in Fort Severn in present day Ontario. In 1787 George carved his name on a rock at Sloop Cove near Churchill.

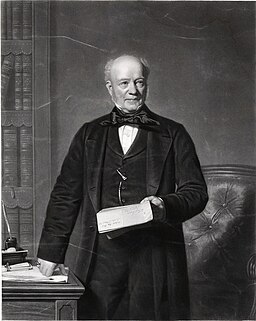

George Taylor and Jane had a relationship “à la façon du pays” (in the custom of the country) and had nine children. Several of their children would be involved with the HBC and the fur trade. One son, Thomas Taylor, became the personal servant of Sir George Simpson. That is likely how Sir George came to meet young Margaret, Thomas’s sister, and make her his “country wife”. How did she feel when she caught the attention of one of the most powerful men in all of Rupert’s Land, the name given to the vast tract of land controlled by the HBC (which is now one-third of Canada)? Was she flattered, charmed, nervous? Was being his “country wife” a happy experience?

Simpson apparently had had several liaisons with First Nations and Métis women before beginning his relationship with Margaret about 1825. Simpson was known to have acknowledged Margaret’s brother, Thomas, as his “brother-in-law”.

Margaret bore Governor Simpson two sons. Their first son, George Stewart Simpson, was born on the 11th of February 1827. In July of 1828 Margaret accompanied Simpson on a canoe trip from York Factory to New Caledonia (what is now British Columbia). Amable Hogue was part of the crew of this trip. During this voyage, Margaret became pregnant again with Simpson’s child. James Raffan states in Emperor of the North:

“In fact, she had re-crossed through the April snows of the treacherous Athabasca Pass when well into her second trimester. Ninety miles on foot or on horseback slogging over her beloved governor’s muddy winter road between Fort Assiniboine and the North Saskatchewan likely did nothing to improve her feeling of well-being.”

Simpson left her at Fort Edmonton, in what is now Alberta, with instructions to Chief Factor John Rowand to arrange for her to go to Fort Alexander, the HBC fort on the Winnipeg River in northern Manitoba, where Simpson’s second son, John Mckenzie Simpson, was born on the 29th of August 1829. A February 1830 letter from John Stuart, Chief Factor of Fort Alexander, to Simpson praised Margaret:

“…it is but common justice to remark that in her comportment she is both decent and modest far beyond anything I could expect or ever witnessed in any of her country women. She appears to be as content as is possible for one of her sex to be in the absence of their lord and natural protector and as a mother she is most kind and attentive to her children whom she keeps very clean.”

There was a great deal of surprise then, when in May of 1830 Governor Simpson returned from a trip to England with his new wife, his cousin Frances! Colleagues were shocked at Simpson’s cruel and dismissive treatment of Margaret. Simpson’s marriage to Frances is considered by historians to be a turning point in the social customs of the fur trade. Whereas First Nations and Métis wives were at one time considered invaluable for their skills and connections, only European women were now “civilized” enough to be wives for the elite in the expanding settlement.

Governor Simpson belatedly arranged to have Margaret married off to Amable Hogue, his frequent crew member and the 3x great-grandson of the Fille du roi, Louise Senécal. They were married on the 24th of March 1831, at St. John’s church in the Red River settlement, now Winnipeg. Amable worked as a mason on the building of Lower Fort Garry, where Simpson and Frances were going to live… how ironic!

Whatever feelings Marguerite (as she was called after marrying the French-Canadian Hogue) had at this turn in her fortunes we will never know, but we do know that she and Amable made a life for themselves in the Red River Colony and raised 10 children. These Métis children married into other families, many of whose descendants populate Western Canada. Amable died in 1858 and Marguerite in 1885. Marguerite is buried in St. Charles cemetery in Winnipeg.

Louise Senécal, a Fille du roi, and one of the many Founding Mothers of Québec, is my 7x great-grandmother. Marguerite Taylor, a Métis, and one of many Mothers of the Métis Nation, is my great-great-grandmother. Two very different women, two very different eras, yet both played a role in important parts of our history. As Canada struggles on our journey of Truth and Reconciliation with First Nations, we would do well to honor these connections.

Sources

Brown, Jennifer S.H., Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. UBC Press, 1980.

Fichier Origine website https://www.fichierorigine.com/

File: Sir George Simpson.jpg. (2022, June 11). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 18:15, July 2, 2023 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sir_George_Simpson.jpg&oldid=663675172.

Gagné, Peter J., King’s Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, 2 volumes. Quinton Publications, 2001.

Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Biographical Information Sheets. Winnipeg, Manitoba.

LaForest, Thomas J, Our French-Canadian Ancestors, v16. Digital edition available at FamilySearch.

Migrations website http://www.migrations.fr/

PRDH Research Programme in Historical Demography (Programme de recherche en démographie historique) website https://www.prdh-igd.com

Raffan, James, Emperor of the North: Sir George Simpson and the Remarkable Story of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Phyllis Bruce Books, 2007.

Van Kirk, Sylvia, “Many Tender Ties”: Women in Fur-Trade Society in Western Canada, 1670-1870. Watson & Dwyer Publishing Ltd.